If you are a Christian and you’re attentive to God’s earth, it’s likely that you’ve sometimes felt on the fringe of your church. In fact, you can feel downright alone. This is one of the reasons I thought it important to write this piece based on my visit to the Au Sable Institute last month. I thought it important, too, to describe the organization and its people in some detail. I hope you’ll persevere through the odyssey of reading this long piece. For decades an organization of committed Christian scientists has been equipping other Christians for ecological research and for science-based stewardship.

They were as surprised as I was.

On Friday, August 4th I made the long drive from northeastern Illinois to Mancelona in northern Michigan to take part in the Au Sable Institute’s Reunion. “Reunion,” of course, suggests an event for people who have had some sort of previous and direct relationship with the institution. Almost every attendee I met courteously asked when I had attended as a student or had taught as a professor. They were astonished to hear that this was my first visit.

In the case of the Au Sable Institute of Environmental Studies, my only previous interaction had been several donations my wife and I had made in the past after a friend had encouraged me to check out the organization. The Institute’s mission – to inspire and educate people to serve, protect, and restore God’s earth – resonated with us.

I decided to visit because I wanted to learn more about Au Sable, and I wanted to be with other Christians who care deeply for the fate of Creation.

Of course, I must be honest that there was a little voice in me wondering if I was going to be in a very awkward situation. I nervously joked with other attendees that I was relieved to hear that there were no secret initiation rites.

One of the things that had tipped the balance toward me attending was a conversation I had had with Fred Van Dyke earlier in the summer. Au Sable’s executive director and co-author of Redeeming Creation: The Biblical Basis for Environmental Stewardship, Fred was kind enough to speak with me on the phone and shared the Institute’s mission with sincerity and passion.

Fred Van Dyke, executive director of the Au Sable Institute of Environmental Studies, speaks during a tour.

From Fred and from the activities of the weekend, I learned that the Au Sable Institute of Environmental Studies pursues its mission by offering environmental science programs for students and adults of all ages. In addition to its main campus in northern Michigan, the Institute has locations in India, the Pacific Northwest, and Costa Rica that carry out similar activities.

The heart of Au Sable’s education mission has long been university-level courses in environmental studies and environmental science that are primarily taught in the field. These courses are accepted for credit by 60 Christian colleges. College students take the classes on Au Sable’s campuses.

The Institute, I’m happy to say, has also been expanding into field-based research around practical topics related to conservation, ecology, and restoration. One example – researchers at Au Sable have been testing different planting practices for restoring abandoned oil pads back to forest in northern Michigan.

If my memory serves from a conversation I had there, there are approximately 50,000 of these sites where forest was cleared for oil pumping. Oddly, forests have not reclaimed these sites many years after the machines and other vestiges of human activity had been removed.

“The Blogger” Feels At Home

The first event that Friday evening was a dinner in the rec center. I didn’t know anyone. With flashbacks to my freshman year of high school running through my head, I set my things down at an empty table.

When I returned with my food, I found I had a number of table companions, including Dr. Calvin DeWitt, the long-time director of Au Sable. From that point on and through the rest of the weekend, I found myself in fellowship with other Christians who talked passionately about beavers and the cloud forests of Guatemala, who prayed humbly, and who were ready to sing the doxology at the drop of the hat. And, I’m happy to say, the food was very healthy. Careful attention was paid to recycling and composting of waste.

Common meals during the reunion were held in the Rec Center. The sliding doors opened wide so we could take in the sights, sounds, and smells of the North Woods just outside. When the campus was being designed, there had been a proposal by a planner to create a typical campus by clearing much of the woods around the buildings. Thankfully, that idea was rejected. The campus is nested in the forest.

What a delight to fully feel at home and in one spirit with other believers!

There was consistently warm hospitality throughout my time there. I wasn’t known by anyone, and yet people came up to me on a regular basis to introduce themselves and learn more about me. I suspect this is what early Christians experienced as they traveled throughout the Roman Empire and visited local churches.

When Cal DeWitt used some of his introductory remarks that first Friday evening to ask for newcomers to introduce themselves, he made a point to ask me to share the name of my blog for everyone to hear. I later learned that from that moment other attendees began to refer to me as “the blogger.” This was done with a mixture of curiosity, intrigue, and perhaps a bit of anxiety.

Calvin DeWitt

A considerable amount of the reunion was spent honoring Calvin DeWitt and for good reason.

Under the lealdership of Dr. Howard Snyder, the Au Sable Institute began as a science camp and field station. It was Cal, as the founding Executive Director from 1979 to 2004, who led Au Sable’s transition to its current identity and wide impact. He did so while serving as Professor in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His curriculum vitae runs over 30 pages, dense with listings of papers and presentations.

He was one of the early articulate voices advocating for Christians to be good stewards of Creation. Through his books and lectures over the past decades, he led the way in articulating the theological underpinnings of why Christians should care and act for God’s earth.

Here’s how an article in Grist summarizes his impact and leadership:

A respected scientist with advanced degrees in biology and zoology, DeWitt spent over 25 years as director of the Au Sable Institute of Environmental Studies, where he worked to help college students learn the principles of Christian environmental stewardship alongside hard science. He’s been one of the prime movers behind almost every significant collaboration between evangelicals, scientists, and politicians, including the much-discussed Evangelical Climate Initiative, a statement from high-profile evangelicals calling for concerted action to battle global warming.

Interestingly enough, he was appointed to his professorship at the University of Wisconsin in 1972 without being placed in a department. His mission was to integrate learning across disciplines.

That focus on integration is one of his most distinctive qualities. He is a dynamic person who delights in bringing together various fields of academic study, especially the sciences, even as he delights in the understanding of the Bible and theology. He loves the pursuit of knowledge and sharing that knowledge with students through teaching.

His breadth of knowledge and the extent of his leadership impact on Au Sable were clear during a tour he led of portions of the campus.

When the tour started at Earth Hall, Cal highlighted the many thoughtful features of its environmentally-minded design that he and the architect worked out together. He rattled off scientific names for most of the living things we saw when the tour then made its way into the woods and along the pond. He stopped to described the construction techniques of a log cabin built for lumberjacks. At a lecture hours earlier, he had lucidly explained the root meanings of Greek words in the New Testament.

He is full of enthusiasm, erudite knowledge, contagious energy, playfulness, and skilled storytelling. What a difference God has made through him.

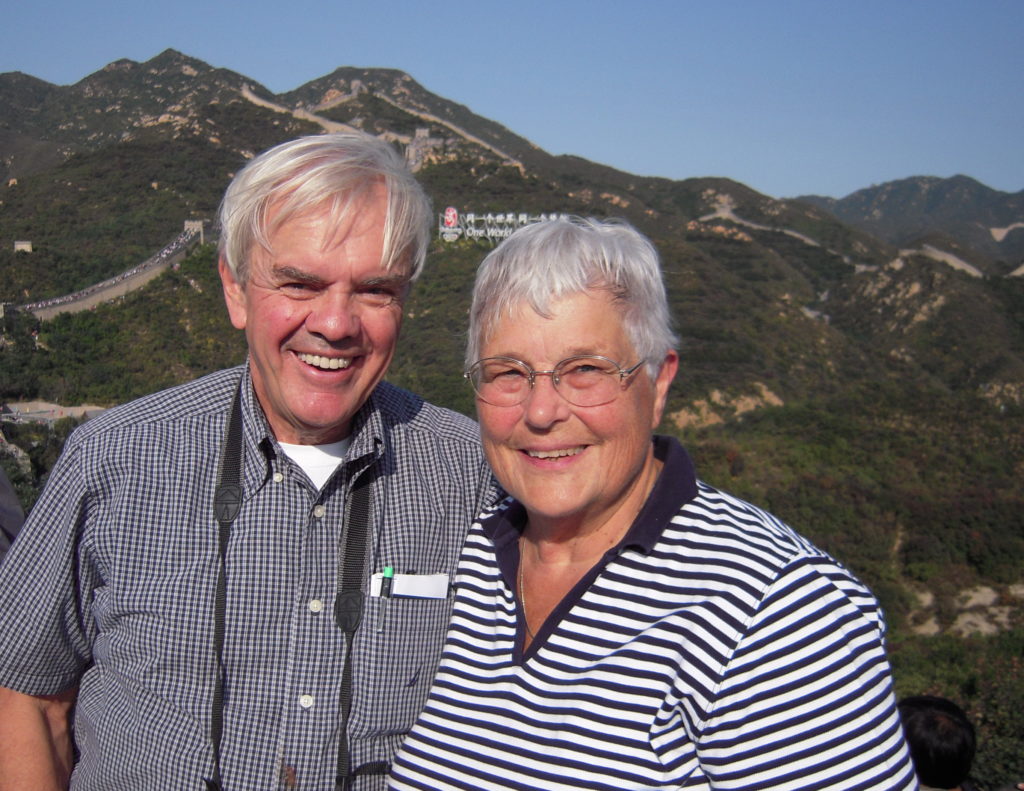

Cal and Ruth Dewitt were kind enough to share this photo of themselves with me for this post. The background, by the way, is not northern Michigan but northern China. You can see portions of the Great Wall in the background.

It would not do to mention Cal without mentioning his wife Ruth. They share a close bond. She spoke proudly to me at the first dinner of the details of the Agricultural Conservancy Zoning that are part of the Land Use Plan of the Town of Dunn. Cal played a leading role in developing this plan which has kept their home town in Wisconsin from being overwhelmed by unplanned development.

When the weekend’s activities closed and Cal and Ruth were walking together towards their car, I noticed they were holding hands.

From Nearly Changing Majors to Restoring Lake Sturgeon

Au Sable changed the life of Marty Holtgren.

Marty was studying biology at Bethel College in 1991 when Dave Mahan, the director of the Au Sable Institute at that time, came to introduce students there to Au Sable’s educational offerings. This intrigued Marty. Many of his fellow biology majors were headed towards nursing careers, but he wasn’t sure biology was for him. What’s more, Bethel’s small size meant that it had few specialty courses in biology or ecology.

In the winter of 1991, Marty attended a summer term at Au Sable. While there, Marty took a limnology course as well as a fisheries course taught by Fred “Fritz” Erickson. This experience led Marty to stay in biology.

“The passion that Fred brought towards fish and other aquatic creatures,” says Marty, “made it hard not to get incredibly fired up. It was contagious. That contagiousness is something that I’ve really tried to emulate throughout my life and career.”

After graduating from Bethel in 1992, Marty worked at the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) for about five or six years. During that time, Marty returned to Au Sable to attend a three-week intensive stream ecology classe. Desiring greater challenges and the opportunity to grow professionally, Marty decided to enter graduate school at Michigan Tech University. There he earned a master’s degree while studying lake sturgeon.

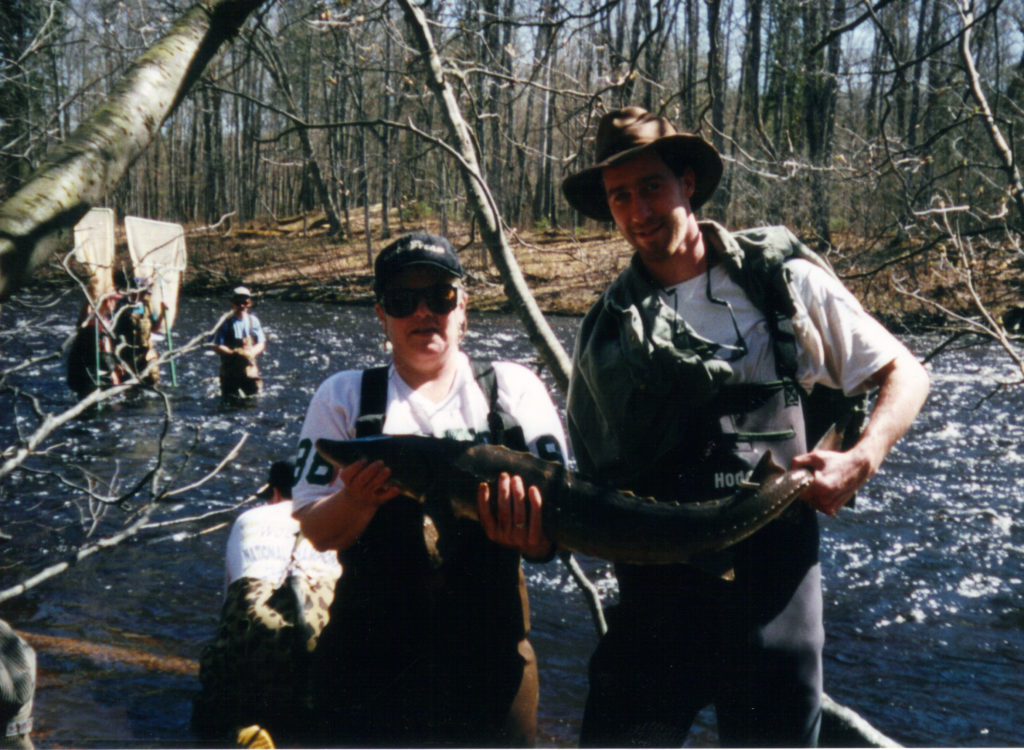

Marty Holtgren, on the right, helps hold a lake sturgeon along the Big Manistee River. For ten years, Marty helped the Little River Band of the Ottawa Tribe, restore the population of this fish species in the river.

This was the springboard for him to then begin working for the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians in Manistee along the eastern Lake Michigan coast. Marty served as their fisheries biologist. In that role, Marty assisted the Little River Band in carrying out a restoration project for lake sturgeon in the Big Manistee River.

“It’s a fish that looks like a dinosaur,” says Marty, “and lives to be 50 years old and can get to be a hundred pounds. They were almost extirpated at the turn of the century. They were also a key cultural species for the Native Americans across the Great Lakes.”

The Little River Band had one of the few populations of lake sturgeon left.

But they didn’t know how many.

“Because it’s not a sport fish, the sturgeon has gone unnoticed and hasn’t been researched much,” says Marty. “So when I started there, I was charged with helping to understand this population and to also labor to restore it.”

The Little River Band and Marty worked for ten years on the restoration efforts. If you were to reduce the restoration to a simple recipe it would be this:

Step One: Capture the young lake sturgeon fry that had just hatched and were heading out to Lake Michigan. They’ll be about an inch long and vulnerable to being consumed by other fish.

Step Two: Raise them through the summer in a portable stream-side facility that you’ve designed, rather than moving them to a hatchery somewhere else in the state. (The Little River Band wanted to keep them in their own watershed where they belonged.)

Step Three: Release them back into the river when the fish are now larger and better able to fend for themselves.

What was even more notable is that the release was turned into an annual community event. The tribal community and their non-tribal neighbors would gather together along the river in solidarity for the fish and the restoration. Then many of the attendees were able to release the lake sturgeon into the river by hand.

“It was a very significant and spiritual moment for me,” says Marty. “You had come full circle with this little fish that you had held in your hand in May. Now you’re releasing that fish four months later and it’s eight or nine inches long.”

“It also healed that community. There was a lot of mistrust in tribal and non-tribal people. You saw healing in those communities. It was a beautiful moment.”

This experience prompted Marty to return to Michigan Tech for a PhD that integrated fisheries management with the social sciences. This integrated approach was valuable because fisheries issues are community issues.

Marty became a tribal liaison for the state of Michigan around natural resource issues. Three months ago, he launching his own ecological restoration consulting firm – Encompass Socio-Ecological Consulting, LLC.

“The main projects I’m working on now are reconnecting people to their watersheds,” Marty says. “On two of the projects I help with large scale dam removals, making sure the public needs are incorporated into those designs.”

“After leaving the Au Sable Institute,” Marty says, “I really had a passion for environmental work and that human connection with environmental work, too. I looked at Creation more holistically and saw that as we’re good stewards we’re also helping the human condition. Au Sable really changed my trajectory.”

The Au Sable Instiute in the Anthropocene

How could I not feel complete delight spending time in the quiet, beautiful woods of northern Michigan with faithful, friendly, thoughtful, stewardship-minded Christians?

Leave it to a blogger with some Norwegian lineage raised in a Missouri Synod Lutheran home whose father frequently reminded his sons not to praise the day until the evening.

Leave it to someone who listened to The Sixth Extinction on the way to the event.

In that book, Elizabeth Kolbert highlights the breadth and astonishing, accelerating pace of species extinction in our world today. She tells the story of how Nobel Prize winning chemist Paul Crutzen was the first to christen our current geological epoch as the Anthropocene. That designation communicates that we are in a new period of life on earth. It is a period defined by massive, geological-scale, human-caused changes. These changes have been largely tragic for the living systems and living beings of God’s earth.

With those kinds of thoughts running through my mind, I couldn’t help but notice that throughout the time I spent at Au Sable I hardly heard a note of outrage or collective sorrow about all that is happening around us. All I remember hearing was the phrase “poor earth” in a prayer.

When I shared this reaction with Fred, he had a thoughtful response I want to share with you:

…I thought you were a little hard on the Institute for a perceived lack of expression of outrage over what humans have done to the Earth and what Christians have done. Some of our symposium speakers did express some of these ideas on Thursday at the symposium, and I have expressed this at times in my own writings. However, at the institutional level, we at Au Sable have found little good to come of outrage over a problem once the damage is done. Hence, our response is more intentionally solution oriented, particularly in our research.

One can express outrage over oil-related deforestation, but that won’t bring back any trees. Instead, we are now determining (and at some levels, already have determined) the best treatments on these oil pads and the best species to plant to restore them to becoming again a living part of the forest community. Similarly, we feel deep sorrow that a beautiful fish, the Arctic grayling, was extirpated from Michigan waters by habitat degradation inspired by greed in Michigan’s logging era. Our response now is to work with Michigan Technological Institute (Michigan Tech) in creating a habitat suitability model that will help identify the best sites for grayling reintroduction.

Likewise we have been saddened by the near extirpation of the Kirtland’s warbler through the loss of young jack pine stands, but encouraged by its recovery which will likely soon lead to its delisting. Our contribution here, which is future oriented, is to determine the warbler’s success in red pine habitat (which it also uses) and, if reproductive outputs are similar (initial data show that they are), create plans attractive to the forest products industry to manage red pine (a more economically valuable tree than jack pine) for warblers, filling a void of support that will occur when the delisted Kirtland’s warbler loses federal protection and federal funding for its habitat management, and making the activity of logging, which once contributed to the warbler’s decline, now an agent of its recovery and restoration.

…I do believe it is better to light a candle than curse the darkness, and better to solve a problem than complain about the harm and hurt the problem caused.

There is no question in my mind that the Au Sable Institute is indeed a uniquely valuable candle.

As I’ve pondered Fred’s words, however, it occurs to me that the culture of science tends to be largely left-brained. It is a culture of rationality, analysis, and calm logic. Those qualities are certainly powerful.

Yet, the words of Aldo Leopold also ring true to me: “One of the penalties of an ecological education is to live alone in a world of wounds.”

Leopold was a man of science and a man of action. But in these words you also hear that he was a man, a man of feelings.

Reading the Bible one is struck by the emotional intensity of the people called by God across many centuries. Jesus himself embarked on a path destined to offer a saving way to humanity and ultimate redemption of all Creation. On that path, Jesus taught the “science” of God’s kingdom but also expressed a variety of emotions as he lived out his mission. In fact, his emotions, many of which were not the happy and calm ones, were part and parcel of his compelling nature.

In the Anthropocene, I believe being fully effective in addressing the wounds humanity has inflicted on God’s earth will require an integrated response that is both left-brained and right-brained.

Without question, we must have the left-brained understanding of how the world works and how to restore it. But right-brained responses are needed as well. We must be creative, emotionally open, and ready to engage in culture and art. The tragedy we face is in large part a product of polluted, closed, and misguided hearts. The unfolding tragedy is also taking its toll on people’s hearts. We must be able to understand, restore, inspire, and connect with people as living souls. We need science knowledge and heart knowledge.

Along these lines I was happy to hear from Fred that the Au Sable Institute is developing programs to train students in leadership. I am hopeful that these programs will begin to help Christians attending the Institute to inspire and lead within human communities, human organizations, and human systems.

Preparing to Leave

When the official activities came to a close on Saturday evening, I parked in the Au Sable Institute’s ball field near a few other attendees who had set up their tents. I slept less than well in my van. On Sunday morning, after a light breakfast the Institute provided, tents began to be broken down, and the campers prepared to go their separate ways.

Voices rose and people gathered when one of the campers, an alumnus of the Institute, spotted a large spider. It was crawling on the fabric of her tent that was lying on the ground and about to be packed away.

We gathered round, children and adults, to take a closer look. There was common curiosity and fascination. When we were done, the orbweaver spider was allowed to go safely along on its way. Once in the dew-flecked grass, it was almost impossible to see.

A simple yet profound Sabbath moment at the Au Sable Institute. An example of the culture I’d love to see be the norm in Christian communities.

We warmly wished each other well, and I departed.

I was glad I had come.