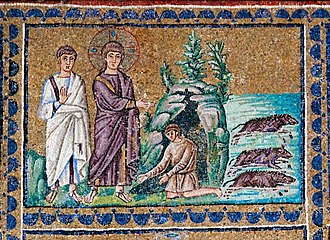

My post about the Bible story involving the pigs, demons, amd Jesus has somehow ended up being the most popular article I have written.

This popularity, along with the the diversity of comments, tells me two things. First, this story from an ancient time and from three of the gospels is still profoundly provocative. In it, Jesus shows powers and a beyond-human presence. He is no mere wise man. Demons, which for 21st century readers raise all kinds of questions, also appear.

And there are the pigs.

Interestingly, we don’t see Jesus interacting with animals very much in the Gospels (although the story from Mark 1:12-13 is very significant), and even here he does not directly do so. We want to ask Jesus, “Do animals matter to you?” I want to ask him, “As someone from a Jewish agrarian society, what did you think when you saw the pigs?”

We have complicated perceptions of pigs, too. In Charlotte’s Web, we sympathize with a gentle, intelligent animal. Yet, we also associate pigs with many negative attributes. We don’t want to be called a pig.

In the story, the massive herd of pigs die suddenly and violently. Their death is clearly connected with the demons being allowed to go into them. But here it’s not clear from the story whether the pigs are passive creatures who are only acted upon in the story or whether they have volition of their own.

Even more strangely, as I have already written, we know pigs can swim. So how could they drown?

And this is where Biblical storytelling creates mystery as well. The story gives us discrete data points. It doesn’t give us a clear statement that explains how those data points fit together. It is up to the reader of the story to discern what that interpretive thread should be.

The second conclusion I gather from the interest in what I have written is that people are not convinced by the standard theological explanations of the story. Despite what many theologians and pastors have said, people with common sense and a heart for God’s Creation have a hard time accepting that Jesus would care nothing about the pigs.

All of this has made me even more curious about alternative readings of the story.

So when I came across one such interpretation in the book by Norman Wirzba entitled This Sacred Life, I wanted to share it with you.

Norman Wirzba is, by the way, someone I deeply admire. He is the Gilbert T. Rowe Distinguished Professor of Christian Theology at Duke University and Senior Fellow at Duke’s Kenan Institute for Ethics. He has also written books like Agrarian Spirit: Cultivating Faith, Community, and the Land and From Nature to Creation: A Christian Vision for Understanding and Loving Our World. And I am just scratching the surface of the attention he gives to Creation in his thinking and writing.

So I was surprised to find myself disagreeing with one key element of his interpretation.

Let’s have you judge for yourself. Wirzba’s interpretation appears in a footnote that is just one large paragraph on page 171 of This Sacred Life. I’m sharing it below and have taken the liberty of dividing it into paragraphs for easier digestion:

“Readers of this story are often puzzled and dismayed that Jesus allows the demons (at their own request) to enter a large herd of swine that numbered around 2,000. Upon entering the swine, the whole herd ran down a steep bank and into the sea (or lake) where they drowned.

Why did Jesus allow this? Does Jesus really hate pigs? It is, of course, difficult to know exactly what Jesus was thinking at this moment, but one plausible interpretation would suggest that the death of the herd was Jesus’ indictment of intensive and abusive forms of ancient Roman agriculture practiced on latifundia in the provinces and around the Mediterranean that were known to degrade the land, creatures, and farm workers (many of whom were slaves). To raise a herd that size, the best that a pig can do is register as a “unit of production” (to borrow a term from today’s industrial agriculture).

It is important to note that Jesus did not send the demons into the pigs. The demons asked to be located there, sensing (perhaps) in the pigs’ abusive condition a place where their violent, demonic ways would be at home. If this interpretation is correct, then this story expands the scope of Jesus’s concern for the integrity and value of creaturely life beyond the man to include the pigs as well. Jesus, in other words, seeks to undo the powers that degrade people and pigs.”

There is much in Wirzba’s book that has enriched my understanding of the connection between God, humanity, and the rest of Creation. In particular, he highlights our “creatureliness.” We, like the rest of Creation, have been created. We are created kin. And the life we and all other creatures enjoy is sustained by God. Life, in other words, truly is a gift that we share in common with the rest of Creation.

It is out of that view of Creation that Wirzba’s theory comes.

I’m completely in alignment with that frame of thinking. I do believe that Jesus’ ultimate mission and purpose is to undo and defeat the evil in the world that degrades people and other living things. Jesus redeems people in part so they can be the stewards and humble shepherds of Creation they were meant to be.

Yet, I ultimately disagree with this interpretation of this specific story. Essentially, his interpretation asserts that by permitting the destruction of the pigs by demons Jesus was indicting the inhumane treatment of the pigs within the Roman latifundia system.

That, to borrow a phrase from the Vietnam war, is like bombing a village to save it.

Wirzba’s thinking seems to be based on the assumption that the size of the pig herd was unusually large and abusive. In fact, from what I can tell, large flocks and herds were not unusual in ancient times. As this blog post from the website The Theology of Work reminds us, Jacob made a gift of at least 550 animals to Esau in advance of them meeting again after many years of being apart (Genesis 32:13-15). From the fact that in the story the pigs did not appear to be fenced in, the pigs very likely had the ability to move about and enjoy fresh air and sunlight. This is completely unlike factory farms today.

Nor are large numbers of animals on a landscape inherently damaging to the land. An example of this is White Oak Pastures in rural Georgia, a farm run by Will Harris. View this video to get a sense of the scale of the thoughtful stewardship going on.

I don’t mean to be critical of Wirzba’s concerns and sensitivity to the pigs in the story at all. We have a tendency to bring our current concerns with us when we venture into the texts of the Bible. That’s not wrong. It’s entirely human. I’ll admit I do the same thing. But what we need to do is ask hard questions. Are, for example, the ancient texts and contexts of the Bible addressing those concerns in the ways we are thinking about them?

In this regard and in connection with this particular story, I have much more of a problem with the cultural blndness of Saint Augustine of Hippo than I do with Wirzba’s suggestion.

Here is a quotation I’ve found attributed to Saint Augustine in several places on the Internet (yes, I know i need to get a more specific notation) in regard to this story:

Christ himself shows that to refrain from the killing of animals and the destroying of plants is the height of superstition, for judging that there are no common rights between us and the beasts and trees, he sent the devils into a herd of swine and with a curse withered the tree on which he found no fruit.

The lack of nuance in this statement is breathtaking. The cruel callousness towards the life of God’s world is stunning.

A key nuance that Saint Augustine missed and that Norman Wirzba and others have noticed is that the demons asked to be allowed to go into the pigs. They were not driven there. How could Saint Augustine make the argument he did? I’m convinced that the forces of culture around him prejudiced his judgement against what is actually in the 66 books of the Bible and what open hearts can tell us.

This brings us back to a central theme of my past years of study and writing. Christians have demonstrated a lack of discernment in reading the whole Bible in relation to Creation for centuries now. We have also had a weak, shallow, narrow idea of what we are redeemed by Jesus for and for what role humanity was originally created. The result is that we ignore Creation or, even worse, rationalize the grinding of Creation under our heels.

This, I’m coming to believe, is why the interpretation of this puzzling, provocative story matters so much.