I was reminded again of the surprising things you can find in the Bible when I read this about Solomon:

God gave Solomon wisdom and very great insight, and a breadth of understanding as measureless as the sand on the seashore. Solomon’s wisdom was greater than the wisdom of all the people of the East, and greater than all the wisdom of Egypt. He was wiser than anyone else, including Ethan the Ezrahite—wiser than Heman, Kalkol and Darda, the sons of Mahol. And his fame spread to all the surrounding nations. He spoke three thousand proverbs and his songs numbered a thousand and five. (33)He spoke about plant life, from the cedar of Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of walls. He also spoke about animals and birds, reptiles and fish. From all nations people came to listen to Solomon’s wisdom, sent by all the kings of the world, who had heard his wisdom. (1 Kings 4:29-34)

This passage highlights two ways Solomon expressed his wisdom, and they seem to be of equal impressiveness to the writer. One is his creative output – 3,000 proverbs and 1,005 songs. This is the Solomon we often hear about. This was the king with a discerning mind. This was the king who was also a musical artist.

The other way Solomon expressed his wisdom is one we typically overlook – the sharing of observations about the natural world.

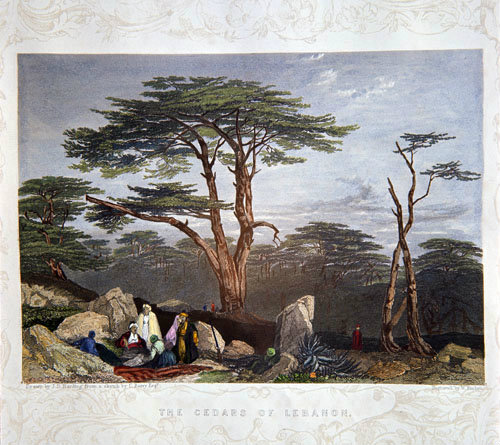

One thing that is striking about the first sentence in verse 33 is the juxtaposition of the two plants. The cedar of Lebanon is a beautiful, majestic tree that used to blanket many of the mountains in the region and was of tremendous economic importance for the Phoenicians, Egyptians, Israelites, and other ancient peoples. In contrast, Solomon also paid attention to a small flowering plant, the hyssop, and the kind of habitat in which it could be found. (For more on the hyssop, look here and here.)

In other words, King Solomon paid attention to plant life in all its variety and diversity. As a plant geek of some degree, I’m heartened and impressed.

It’s striking, too, that he paid attention to the whole diversity of creatures, not just those of practical value. Reptiles are a great example.

The Bible is known for its economy in storytelling, but I very much wish we could read more of what King Solomon said about plants and animals and how he gained that knowledge.

One inference I would make from verse 33 would be that not only did Solomon speak about plants, animals, birds, reptiles, and fish but that his wisdom about the natural life around him ultimately came from close personal observation. This, too, tells us something about Solomon. Observing and understanding the natural world takes patience, prolonged concentration, humility, and attention to the interplay of many different factors. Doesn’t that sound like an ideal foundation for developing wisdom?

And might his father, King David, have tried to impart his knowledge and fascination with the natural world to his son? David had been a shepherd and likely had been fascinated by those same plants and creatures that King Solomon was.

If I was to take this train of thought far beyond what any text might support, I would suggest that not only did King Solomon observe plants and living creatures carefully, he may also, like a modern scientist, have noticed patterns in their form and behavior that perhaps others had not noticed. Perhaps this is what especially stood out to the people of his time? Perhaps it is also that he paid close attention to the non-human world and saw plants and creatures as wonders?

Again, much of this is conjecture.

But what is worth hanging onto is this – the Scriptures highlight that an important element of Solomon’s great wisdom was his knowledge of the living things of his home region.

This makes me wonder what kind of world might we have if the leaders of churches, businesses, local government bodies, and other human organizations of note today were to know the basics (and the wonders) of the flora and fauna of their place.

I am convinced that if the Church of all believers is to be a true and loving presence in the world then it must hold to and exhibit a whole faith that includes an abiding concern for God’s earth.

For that to happen, the Church’s leaders and the leaders of individual churches must have a whole faith and, like Solomon, be wise in the ways of humanity and all of Creation. And believers who go out in the world to serve as leaders of companies, government bodies, and other organizations must also have faiths rooted in a wisdom that includes attentiveness of the natural world and a deep concern for it.

How do we make that happen?

That’s no small challenge.

Nevertheless, and you can call me an naïve optimist if you like, I look forward to the day when it is the norm for church leaders and leaders who are Christian to speak of the wonder’s of God’s world – of trees and small flowers as well of mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish.