Reverend Nurya Love Parish at outdoor altar during Blessing of the Fields at Plainsong Farm (photo courtesy of Plainsong Farm).

Over the year, I’ve met remarkable people bravely pursuing their own unique path towards a whole Christian life. Nurya Love Parish is one of those people.

Some years ago, I became aware of her and the work she was doing with others around building Christian community around a farm. So I reached out, and she kindly agreed to a chat by phone. I was instantly struck by her faith, her love of God, her cheerful and yet candid way of expressing herself, and her willingness to navigate institutions of Christianity in her calling to serve God’s people and God’s Creation. I knew I needed to interview her at some point for this blog. And when I did, I wanted to share our conversation with you.

What you will read below is an edited transcript of an interview we did in 2023 followed by an additional exchange in 2024 that emerged after the interview (you’ll see why we needed to do a follow-up!). I hope you will come away with two things. One is a story that sticks with you of God being alive in people’s lives in most remarkable ways. Perhaps this will inspire you to listen for your own calling. Maybe even act on the calling that you’ve always known was there.

The second is a set of insights into how Christians like Nurya and the other good people at Plainsong Farm are experimenting with new institutions that bring together collective God-led work and Creation. This is new ground. We need to learn from each other about what works and what doesn’t in unique contexts. We need to be open to new approaches.

I would normally include more biographical information here. Instead, so you can “hear” her words without preconceptions and with more appreciation for her way of telling her story, I’ve set that information at the end of the interview.

Part One: Summer 2023

Nathan: About three weeks ago I read your book Resurrection Matters: Church Renewal for Creation’s Sake for the first time, prompting me to reach out to you. What you’re doing at Plainsong is fascinating and inspiring. I think we’re at a time of transition in so many ways in terms of the Church and the earth. And it feels like Plainsong is right in that space that is also the focus of your book. So I wanted to share your experience and your insights with our readers.

One of the things you make clear very early in the book is that you only attended church one time in your first 19 years of life. Now you are fully immersed, and one of the things that comes across clearly in your book is how much you love church.

Nurya: Aw. I’m glad that comes across.

Nathan: Can you briefly talk about how you came to be a Christian? And was Creation part of how you came to Christ?

Nurya: I would say yes to that. But I don’t know that it would make sense without an explanation. I was a child in Las Vegas and found myself looking at my lawn and realizing that it just did not fit. I was wondering where the adults got the idea that it was a good move to put this many humans in a desert. It didn’t seem wise to me. And looking for wisdom drew me to Christ. I went to church for the first time when I was 19 when I was in college. And very unexpectedly – I cannot begin to describe to you how unexpected this was – I had a call to ministry. I was just going to church. I was just curious about what church was. But the minister came out to start the liturgy, and I just profoundly understood “You’re going do that.”

I’m 19. I don’t know what I’m doing with my life and I’m wanting to know what I’m going to do. I really didn’t think that that “calling” was going to be how it worked. But then the year following that experience, I found out that my father, who had died a couple years previously, had been a refugee from the Holocaust and never told me.

Nathan: Whoa.

Nurya: He was born in Vienna in 1922 and he and his family left Europe in 1939. And those were facts that I knew, but in my childhood I was not raised with any connection to Jewish community or practice. It never occurred to me to put those facts together with other historical facts until I was in my junior year abroad and we were about to visit, as an educational experience, a concentration camp. In the preparation for the visit, we were told, “You’re going to a concentration camp tomorrow, and here’s some of the things we know about the Holocaust.” And for the first time I put together that my family leaving Europe in 1939 was because of the Holocaust. Not the best way to find out.

After that call to ministry and that visit to the concentration camp, I spent a couple of years trying to figure out my religious identity. I spent time in the Jewish community and, weirdly, I missed Jesus.

In the Jewish community, they don’t talk about Jesus. The Jewish community’s not interested in that conversation for good reasons. When I realized I missed Jesus, I found my way back to the Unitarian Universalist world where I had first gone to church. Then I went to seminary and went to Harvard Divinity School. Harvard Divinity School was the first place that I found Christians that wanted to talk about faith in a serious, meaningful, but also open-ended way. It was where I met people who were the kind of Christian that I wanted to become.

I was baptized at 25, my last year of seminary. God provided for me in incredible ways. There was one job for a Christian pastor in the Unitarian Universalist Association the year that I graduated. It was a new church plant in Fenton, Michigan. That’s how I came to Michigan. I got that job.

Nathan: It seems like you had something inside you that resonated with the liturgy, resonated with church and Christianity even before you could kind of put your mind around it. Is that fair to say?

Nurya: Oh, absolutely. Madeleine L’Engle was my kind of pole star writer as a young person, and she was an Episcopalian. She would sprinkle in like snippets of the Bible and quotes from Christian thinkers into her young adult fiction. But the message that I got from the popular culture about Christianity was either you’re a Christian or you’re going to hell. And that just didn’t seem to me like it could possibly be true. So I figured I might not be a Christian then, because I figured you had to believe that to be a Christian. It wasn’t until I met Christians who understood Christianity differently that I realized I could be a Christian after all.

Nathan: So that combination of inner movement and finding the right Christian habitat as far as how people understood the Bible really kind of led to your conversion.

Nurya: Yes. That’s a perfect description. The right Christian habitat. I love that. May I steal that?

Nathan: Sure. [laughter]

Nurya: I’ll try to remember to attribute it, but it is really a great concept. I’m used to thinking about Christianity in terms of traditions and denominations, but it is a tradition we inhabit. In order to inhabit it, we need a habitat.

Nathan: Most Christians who care about Creation tend to come from a more thoughtful, sensitive, selfless approach to life. It’s hard for them to find places where those traits are welcomed and celebrated.

Nurya: Which is so ironic because that is Christ.

Nathan: You should write a book about that.

Nurya: I think that’s my next book. The longer that I’ve done this, the more that I have realized the questions that people have for me are as much about my story as they are about Plainsong. Kind of like you’re asking now: what is it in my story that led to Plainsong Farm?

Nathan: You talk in the book a number of times about career versus life – having a life versus having a career. You encourage the reader to question whether one is seeking one’s own security or responding to needs and responding to a calling. You also talked about church not being about maintenance. That was provocative.

Nurya: Wow. I need to read my book [laughter]. I have forgotten everything I wrote. It sounds like something I need to recall.

Nathan: If you read the Bible, the Bible is full of risk, drama, change, tragedy, movement, dynamism – all of these urgent, moving, compelling things. Somehow typical church has often become about buffering ourselves from life as much as possible and about refining a theory and theology of God that is as pure as possible. And let’s keep doing the model of church the same as much as possible. The disconnect, the cognitive dissonance, between the energy and action of the Bible and how church actually works is huge.

One of the things that really struck me was that you had this calling to create something like Plainsong for a long time. You and your husband bought the 10-acre property, and you thought, “Well, I should start farming first.” But you found out that farming wasn’t necessarily your thing. And so at one point you got on your knees and essentially said, “God, you have to take care of this.” That led you to take a big risk. Can you say more about that moment and just being able to let go and let God sort of lead you and to follow that lead?

Nurya: It’s probably a moment of spiritual crisis that it is good for me to remember. I don’t often get asked about it, because I think it takes a rare person to be interested in somebody else’s dark night of the soul. So thank you for being that person.

It was probably May 2014. I really felt like I had totally failed. Because I had thought that it was my job to make Plainsong Farm. And then I figured out that I couldn’t do it. I am not a farmer. And you cannot have a farm without people who are called to the work of agriculture somehow. I tried, and I found no joy in the work, and I did not understand what God was doing in my life – I was called to this ministry without any aptitude or desire for farming. So I said, “Lord, I can’t do this. If you want this done, you’re going to have to do this. If you do this, I will help.”

Unfortunately, or fortunately, from that day to this, there’s been zero ambiguity that God is bringing Plainsong Farm to life. It has required a ton of help. No disrespect to the Lord, but human beings have to create systems and manage staff and do fundraising and all of that. God can inspire generosity and bring the people, and God has done those things just in incredible ways. But it also required a lot of help.

Nathan: One of the things you talk about is not having the confidence yourself in the calling. And your calling didn’t seem to necessarily resonate with everyone you shared it with.

Nurya: Oh my goodness! I started talking about Plainsong to people in 2008. Tom Brackett in the Episcopal Church, in our office of church planting, was the first person who didn’t look at me like I was crazy. I felt like I was the only person on earth that had this vocation. I was looking for any models that might exist, any organization that might exist, any hope that I was not just utterly delusional. The church infrastructure had no concept for this.

It has been incredible since 2015 to see how many people God has called to do ministry interwoven with agriculture and nature. This is obviously something that God is doing at this point in time. I turned out not to be crazy or alone, but it sure felt like I was both in the early 2000s.

Nathan: I think a lot about what ecclesia should look like as the world changes. It seems like the farm church or farm community is a different way of doing connection. Do you think some of the inability of other people to sort of latch onto your calling was that you were paying attention to Creation and you were also proposing to do church differently?

Nurya: Yes. I think I didn’t have words for it. It was hard for people to understand what I was feeling called to do because I could not explain it. And unfortunately that has even been true in the founding process. The words in our mission statement – I didn’t write any of them.

Nathan: Oh, wow.

Nurya: I said yes to them when I heard other people say them. I was like, “Yes, that’s the thing that God is calling forth. That’s the thing.” My friend Polly was in our early founding team, and she put together the words about cultivating connections. Mike Edwardson, who I call my co-founder (he disagrees), put together the words about nurturing belonging and the radical renewal of God’s world. And I was just like, “Yes, that’s the succinct description of what this is.” But I could not articulate it myself.

I also was always clear that it wasn’t a church. The challenge with that approach though, and this is very fresh thinking [laughter], is that it is and is not a church. It is a community of practice. And it is an unintentional community of practice because it was not founded to be a community of practice. If I had thought that I was founding a community of practice, I would’ve done almost everything differently.

But I knew that Plainsong Farm wasn’t going to persist unless there was an entity that had capacity to take financial responsibility for the property. My family couldn’t afford to donate the property, and the organization wasn’t going to work for the long run unless it owned the property. So I focused 100 percent on creating a viable nonprofit organization that could purchase the properties on which it operates. We completed that work earlier this year.

Nathan: Let’s jump from when you founded Plainsong to today. You’ve said since you wrote the book that you feel like a lot has changed. Plainsong has obviously evolved. Can you say a little bit about what Plainsong is like today?

Nurya: So today I am grateful to say that Plainsong understands that who we are is a living laboratory for farm-based discipleship and environmental education. It took eight years for that to be clear. Partly because I wasn’t clear that that was what this was, even though I wrote a book about it. Partly I think it was hard to get there because it wasn’t something that we could copy from someone else.

When we started, we started with a community supported agriculture (CSA) program and also doing educational programming. As we evaluated our operations, it became clear that our unique contribution was education. And so now we have programs that teach and practice farm-based discipleship. It’s immersive farm-based discipleship programming.

We no longer run a CSA program. Instead, we partner with New City Neighbors, which runs a community supported agriculture program on Plainsong Farm’s land. So we still have agricultural production, and we do it in partnership with another faith-based Christian non-profit that is also thinking through issues of care of Creation, racial justice and reconciliation, and the practice of Christianity.

Nathan: And you now have a lead farmer.

Nurya: Yes, Mike Edwardson. It’s turned out that Mike is not only a lead farmer, he’s also one of our lead educators. Mike did youth ministry at Mars Hill in Grand Rapids back in the Rob Bell days. This has been a learning journey for both of us.

Nathan: How are faith and Christianity integrated into the life of Plainsong Farm?

Nurya: One of our signature programs is the Young Adult Fellowship. The Young Adult Fellowship is a ten-month residential program that is part of Episcopal Service Corps. It’s a residential experience that combines work on the farm with a number of other different roles. The fellows have a rhythm of life that includes daily practices of morning prayer, reflection, and spiritual formation. The fellows also get paired up with spiritual directors. Emily, who is on our staff, runs this program.

We also have, for the general public, the seasonal Sabbath at the Farm program, which is outdoors on Sunday afternoons. There is always a Bible story, always a wondering question, always a hands-on experience and always time for prayer and a potluck. That is something we’ve done from 2017. We started doing it weekly in 2019 for 12 weeks in a row. In 2020 we canceled it because of the pandemic. We brought it back monthly outdoors in 2021, and it was weekly last year.

As far as numbers of people attending, it’s been very up and down. The year 2019 was a little overwhelming, because there were 12 people at the beginning of the summer and then 50 people at the end of the summer.

Honestly, at the end of 2019, I was just like I don’t know how to cope with the growth of this place, which was a very nice problem for a mainline Christian to have. But it was still a huge problem. Then we had a pandemic, we couldn’t gather people, and they scattered. If I were church planting, I would be trying to grow those Sabbath event numbers. But I created a traditional nonprofit structure. That does leave Plainsong with strategic questions that we are in the process of answering now that we’re in this chapter of Plainsong’s life.

Nathan: Can you say more about how has the land, your portion of Creation, evolved from the time you and your husband bought the land until now?

Nurya: Definitely. It was 2001 when we moved here. It had been fallow, but not for long. The people that we bought it from farmed organically starting in the 1980s, even before USDA certification existed. They were part of the original Organic Growers of Michigan mutual certification process. Then they ended up selling to us.

When we bought it, I thought I couldn’t find a job, and we thought we couldn’t have children. And then I was immediately employed full-time, and we had two children!

So with that, it never really got farmed. We just kind of let things go fallow. This caused me to feel like we hadn’t kept faith with this place. It was meant to be a farm. God led us to a different place to live, and a mutual friend introduced me to Mike and Bethany Edwardson. At the time we met, they had a goal to have a farm that was somehow connected to the church. We started working on Plainsong together, and that’s how it came to life.

When we met in 2014, Mike and Bethany were in their twenties. Mike had an incredible amount of agricultural energy. He recreated the fields. He worked with the Kent Conservation District, which led to us getting into the Regional Conservation Partnership program. That funding allowed us to install native species and engage in conservation practices. Mike was making all of those decisions, and he was making decisions in accordance with our shared values. We set off some of the wetlands and just didn’t grow there. We started planting native trees, started planting pollinator habitat, and began using drip tape irrigation and cover cropping.

Now we engage others – volunteers and program participants – in these practices for their own learning and to cultivate connections, to build community. We all share this earth.

Farm Camp at Plainsong Farm – Mike Edwardson shares insights about plants and farming (photo: Plainsong Farm).

Nathan: One of the points you make in your book is that both the church and the climate are in decline. And the church, you assert, can play a special role in addressing creation and all those kinds of issues. What are your thoughts now about the form of Christian community that makes the most sense now in light of everything that’s happening?

Nurya: I feel ambivalent about that question. The church is disciples. It’s not institutions. But I am an institutionalist. I am not an individualist. I am an institutionalist.

Individuals are mortal and so are institutions, but institutions carry meaning across generations. I created an institution to help multiple generations move more fully into what I now understand is the question of our country and our time: how do we practice Christianity in a way that cares for the place that Europeans colonized? I didn’t know that was what I was doing when this all began. I had to get to 2018 – after my book was published – and read Willie James Jennings. I’ve learned a lot as a white person in the last few years.

So the church is disciples, not institutions, and yet disciples inherently are going to make institutions. Somehow we have to make institutions that are focused on the practice of faith and the risk taking it involves. I think we have lost that thread.

Nathan: I’ve read some interesting books, and they talk about how church as we think of it wasn’t necessarily the original way that believers assembled and worked together and lived together. Instead, the way church is traditionally done has some genetics from the Roman Empire. And so the church template, as we have it today, isn’t necessarily the form that it has to be.

Nurya: Yes to all of that. And I say that as an Episcopalian. I don’t know if you’re familiar with us, but we have quite a bit to do with Empire. But also one of the things that I love about the Episcopal Church is we have this weird combination of Empire and Benedictine woven into us.

This place I have always hoped would bring out the Benedictine side of Christianity. That’s why it’s called Plainsong. It’s the only thing I knew. When Mike and Bethany and I sat down for our first conversation, I was like, “All I know is that it’s called Plainsong Farm, and it’s called Plainsong Farm because plainsong is the practice of prayer in the Benedictine tradition. And Benedict left Empire to practice faith in the desert.”

And for some reason, despite the fact that this was all I could tell them, they still signed up, they still wanted to participate. That was grace.

Nathan: So what little things are you getting inklings of in terms of what discipleship-based communities might look like going forward with Creation being part of it?

Nurya: It’s ecumenical.

Nathan: Really?

Nurya: Absolutely.

Nathan: Say more about that. That’s provocative.

Nurya: At Plainsong, our life is an ecumenical life. Our staff is ecumenical. Our board is ecumenical. I think what I’m seeing is people that are part of institutions saying, “My institution is not doing the work that it’s called to do right now. How can I find some other people that are?”

This approach can be very tricky when you’re trying to start an institution affiliated with the Episcopal Church. But I’ve had to remind myself, the Episcopalians, and everyone here that Plainsong is affiliated with the Episcopal Church because we have the parish mentality. It’s where you live, not what you believe that makes you part of this community. It’s a mentality that we inherit from Empire, but it still is a mentality that I think can be redeemed.

Nathan: It’s all still within the Christian set of beliefs. It’s just that you’re flexible beyond denominational lines.

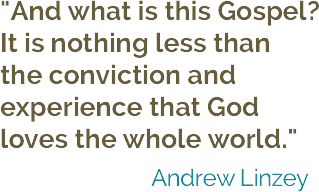

Nurya: Yes. I believe that the world needs a much louder proclamation of a Christianity that makes clear that God made and loves all Creation. And that louder proclamation needs a lot of humans.

And it needs some humans that don’t know those words yet, and yet this idea lives in them. The kind of way that it lived in me. I had felt like something was wrong with the way Christianity was practiced, but I didn’t know how to articulate it. Only by putting myself into this context and trying to learn the things that this context demanded of me did I start to be able to articulate it.

Nathan: Your book was written with the hope that the renewal of church could help renew creation. I’ve been reading some of Professor Jem Bendell’s deep adaptation work in which he argues that government and academia has downplayed how far along we are in climate chaos. There will be disruptions, and things can’t be put back in place. In short, we’ve gone past the tipping point.

So if we’re past that tipping point, does Plainsong Farm (and other experiments like it) point us towards what the next kind of faith community will be in this changed world? Because if we have huge social disruption over time, then, just like monasteries, land-rooted faith communities could be planting seeds for a new civilization…or at least a new form of collective Christian living. I see it in what Plainsong Farm is becoming.

Nurya: I think when we began that is what I was thinking.

Nathan: It’s interesting to see that as we head into this big disruption, there are these people, like you and Plainsong as well as the Hazon movement, who have these yearnings and who are led by God and who sense that we need to have a new relationship with God and a new relationship with Creation.

I don’t think we can persuade established churches and denominations to move fast enough to face this disruption and to rethink themselves and their relationship with Creation. Creation tends to be an appendix to what most churches and denominations think about Creation. Creation is not made an integral part of what it means to follow and love God. They are not prepared for dealing with it at a deep, deep level. So I can’t help but believe we need new forms of Christianity going forward.

Nurya: I literally see us doing that. It’s right there. It’s happening. It is really important for younger generations. One of our alums said we were one of the rare Christian institutions that took her climate issues seriously. And I see it in my kids, too. They are happy here at Plainsong.

And other people seem to really need this place. A couple of years ago, a person sent me a note that essentially said, “I don’t think that I would still be involved with church communities at all if it weren’t for Plainsong Farm.”

Nathan: Wow.

Nurya: Then there’s the environmental educator who decided that she wanted to talk to me about religion. And after we talked about religion, she then came to the church that I was serving at the time. She then had an experience of God with the church and returned to faith practice.

And there’s the young adults who are with us now. This is what means the most to me, obviously, because I didn’t have that. I know how grateful I am that I found a way of life that was a way of faith. And I know how hard it is to find.

Nathan: That’s a beautiful place to end.

Nurya: This hasn’t been an easy journey, but there’s no doubt that other people’s lives, and my life have been very changed. God has worked through this ministry to change the lives of a lot of people. There are hundreds of people that are engaged in one way or another. And there are tens I would say whose life will never be the same and in ways that more nearly reflect the glory of God and in the care of God’s world. So thank you so much for taking this time. I have learned through this conversation, and I appreciate your ecclesiological questions.

Nathan: It’s wonderful to talk to you. I’m so grateful for what you’re doing.

Visitors on tour of Plainsong Farm in fall of 2023 enjoy watching children play in prayer labyrinth.

Spring 2024

Nathan: I understand there have been changes since we last spoke. Tell me what has happened since we had our initial conversation.

Nurya: Whew. I don’t remember when we first talked, but I do know that in my soul last summer I was starting to see that the work that God had called me to do at Plainsong Farm was done. When I began my work on Plainsong in 2013 and 2014, what I was dreaming of and hoping to bring to life… I could see it. It was happening. I would walk the farm and instead of the farm kind of being grumpy and unsatisfied with me, which is how it felt in 2012, or encouraging me along, which is how it felt in the early years of organizing the ministry – 2018, 2019 – instead I started to feel a sense of completion. Not like Plainsong was over – Plainsong was very, very not over – but like what I was called to do had come to its natural end.

When we incorporated in 2019 I had made an agreement with our board of directors that I would remain the executive director through December 31, 2023. So all of 2023 I was wondering, “Am I staying past the end of this year?” The board had kindly invited me to continue. But the longer the year went, the clearer it became to me that it wasn’t going to be good for me and it wasn’t going to be good for Plainsong for me to stay. It became really, really clear the day in September that the board chair sent me an agenda with my contract renewal as an item on the agenda, and I realized that I could not in good conscience allow the board to renew my contract as the executive director. I didn’t have it in me anymore. I needed to go.

Nathan: That sounds like it was a hard place to get to.

Nurya: It was. I love Plainsong Farm. I love the place, and its people, and I love the work. So it was sad. And also, I knew that Plainsong was going to need me to leave without me having something else lined up, because Plainsong wasn’t going to be okay if it had a fast transition. When you leave one job for another job, usually you have like thirty days. Plainsong wasn’t going to be able to make that shift in thirty days. So I just had to say “I can’t renew my agreement” and step back and wait to see what happened. It felt so much just like starting Plainsong Farm all over again: a big risk.

Nathan: Now you have a new role, and Plainsong has new leadership. It sounds like you didn’t know any of that was going to happen.

Nurya: I did not. I knew the role I now hold was available, but I didn’t get offered the job until February. So that was four months without knowing if I would have employment after my work at Plainsong ended. For the first couple of months, I wasn’t really looking, because I wanted to wait to see how long Plainsong would need me. They ended up settling on February 29 as my last day, and that honestly turned out perfectly, because March 15 was the right first day for my new role. But I had no idea how things would work when I said I needed to step down.

On Plainsong’s side, the board and staff created a transition team, and I wasn’t on it, which was exactly right. That transition team ended up with the staff proposing the co-director model. I would never have thought of it, but I enthusiastically support it. The new Co-Directors at Plainsong Farm are Katharine Broberg, Mike Edwardson and Emily Ulmer. I worked with all of them for years and I love that they wanted to step forward into leadership. I couldn’t ask for a better succession plan than the one they made.

The three new co-directors of Plainsong Farm (from left to right) – Mike Edwardson, Katharine Broberg, and Emily Elmer (photo: Plainsong Farm).

Nathan: Tell me a little about your new work.

Nurya: I now work for the Episcopal Dioceses of Eastern and Western Michigan, who voted on March 16 to merge later this year and make a new diocese together, the Diocese of the Great Lakes. It’s funny to look back on everything I said about ecumenism now that I am in such an Episcopal-oriented role. I am still deeply committed to ecumenism, but I feel a call to serve my own church in this next chapter of my ministry. My work is to care for the churches in the northern part of Michigan’s lower peninsula. There are 33 congregations there. In addition, I hold the portfolios for two diocesan-wide initiatives: Building Beloved Community, which is our work for inclusion and belonging, and Care of Creation. It is pretty exciting to hold the Episcopal Church’s portfolio for Beloved Community and Creation Care in ¾ of Michigan’s lower peninsula, but it’s only about 10 percent of my time. So right now I’m pondering how I can use that 10 percent wisely. My priority has to be our congregations. I believe the Episcopal Church has gifts to offer, and for that, we need stronger churches.

Plainsong gave me a beautiful “Blessing and Sending,” and there was a small gathering afterwards where a few people spoke. Mike Edwardson was one of them, and he made a reference to a movie called Interstellar, which I have never seen. But apparently there’s a moment in it where someone is told that something is impossible. And they reply, “It’s not impossible. It’s necessary.” Then they keep going; they don’t give up.

I feel like that sums up so much – about my ministry with Plainsong, about my ministry now. I’m grateful for that story and for all the wisdom and love I received from God through Plainsong Farm.

More on Nurya’s Life

Nurya was born in Las Vegas, Nevada to a nonreligious family and first felt a call to ministry while attending church for the first time as a college student. While attending Harvard Divinity School as a Unitarian Universalist, she was baptized as Christian and later ordained as a Christian pastor within the UUA in 1997. After ten years as a Unitarian pastor and church planter, she realized she was “sneaking off for prayer with the Episcopalians regularly and frequently.” After completing a Certificate in Anglican Studies at Seabury-Western Seminary, she was re-ordained as an Episcopal priest in 2011. Since then, she served as associate rector with St. Andrew’s, Grand Rapids and as priest-in-charge with Holy Spirit, Belmont, while beginning Plainsong Farm.

For nine years, she served as the founding Executive Director of Plainsong Farm and Ministry, an ecumenical ministry in the Diocese of Western Michigan. This year she became Canon for the Northern Collaborative. In this role Nurya will coach, encourage, and equip congregations in Michigan’s northern lower peninsula in areas of congregational development, transitions, and in seeking God’s vision for their future.

She is married to Dave, a retired firefighter, and together they parent two college-age young adults, Claire and Nathan. She is the author of Resurrection Matters: Church Renewal for Creation’s Sake (2018).